Testing the robustness of learned index structures

Published:

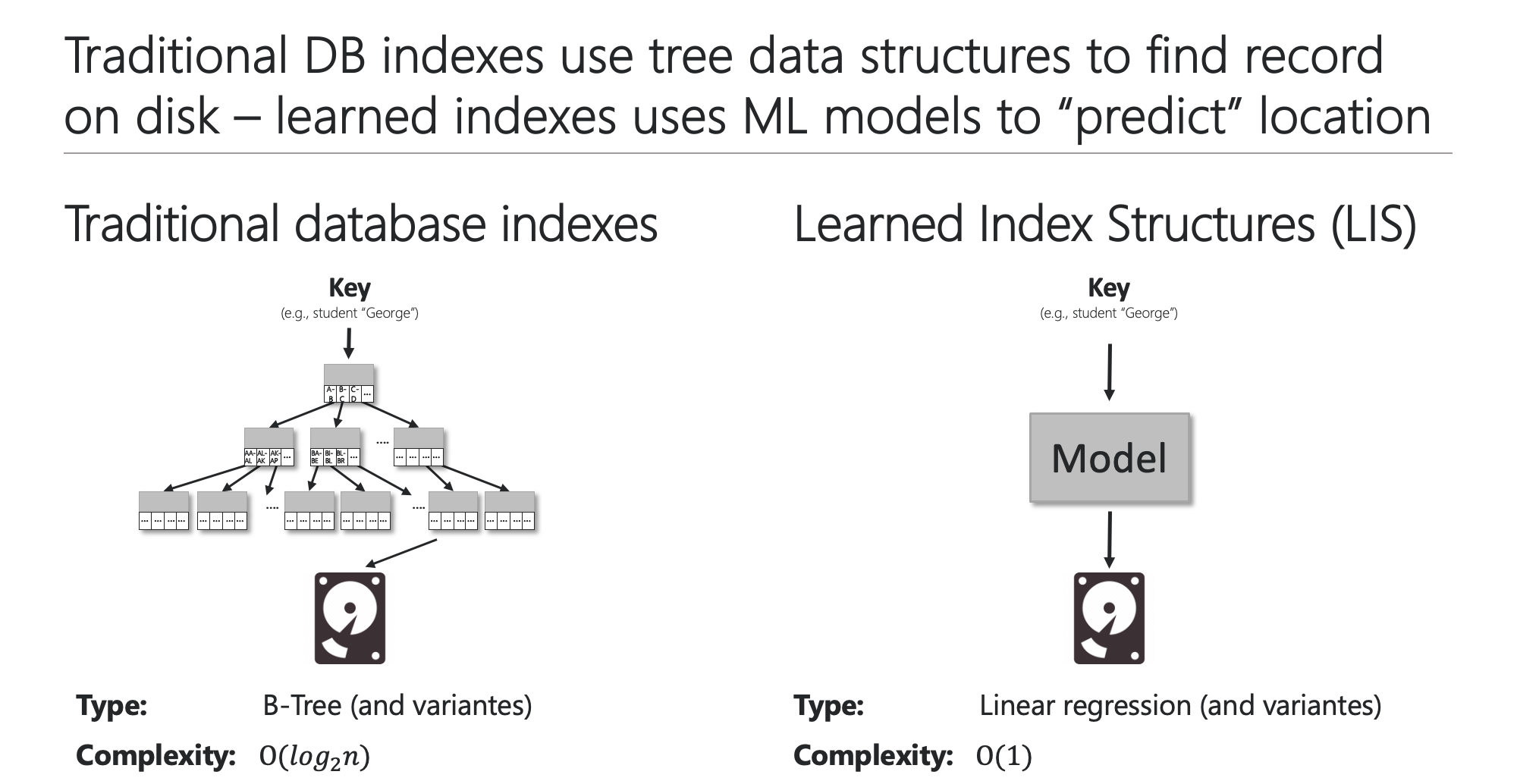

The database community has recently seen a massive surge in research to replace traditional database indexes such as B+ Trees with machine learning models (also called “learned index structures”) to facilitate fast data retrieval.

Databases rely on indexes to quickly locate and retrieve data that is stored on disks. While traditional database indexes use tree data structures such as B+ Trees to find the position of a given query key in the index, a learned index structure considers this problem as a prediction task and uses a machine learning model to “predict” the position of the query key.

| Traditional and learned indexes | ML models to approximate the CDF |

|---|---|

|  |

This novel approach of implementing database indexes has inspired a surge of recent research aimed at studying the effectiveness of learned index structures. However, while the main advantage of learned index structures is their ability to adjust to the data via their underlying ML model, this also carries the risk of exploitation by a malicious adversary.

This post will show some experiments that I have conducted as a follow-up to the research on adversarial machine learning in the context of learned index structures that was part of my master’s thesis at The University of Melbourne.

Previous work on “Executing a Large-Scale Poisoning Attack against Learned Index Structures”

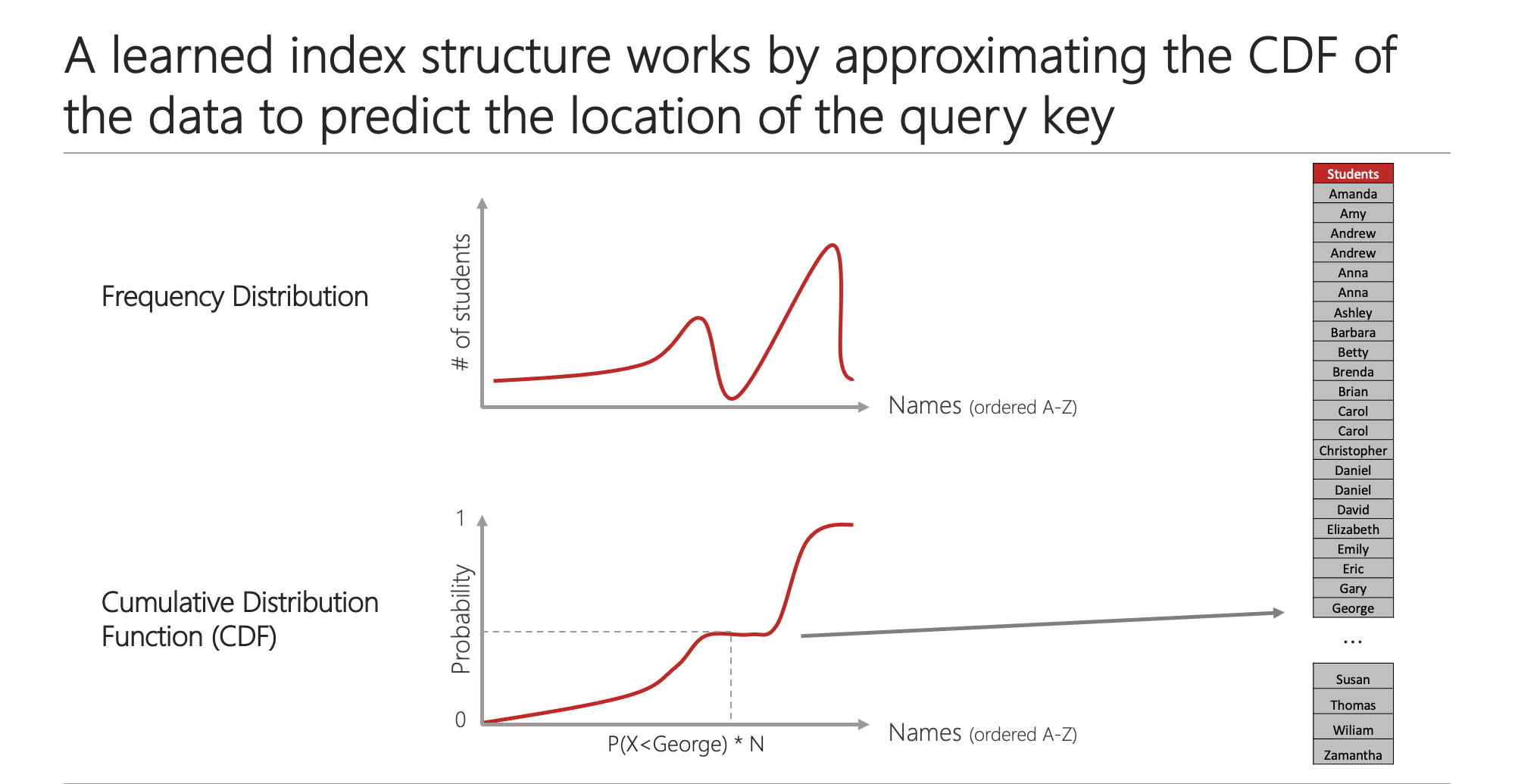

In my master’s thesis, I have executed a large-scale poisoning attack on dynamic learned index structures based on the CDF poisoning attack proposed by Kornaropoulos et al. The poisoning attack targets linear regression models and works by manipulating the cumulative distribution function (CDF) on which the model is trained. The attack deteriorates the fit of the underlying ML model by injecting a set of poisoning keys into the dataset, which leads to an increase in the prediction error of the model and thus deteriorates the overall performance of the learned index structure. The source code for the poisoning attack is available on GitHub.

As part of the experiments for my master’s thesis, I evaluated three index implementations by measuring their throughput in million operations per second. The evaluated indexes consist of two learned index structures ALEX and Dynamic-PGM as well as a traditional B+ Tree. Because indexes are usually used to speed-up data retrieval when dealing with massive amount of data, I chose to evaluate the performance of the indexes based on the SOSD benchmark datasets that consist of 200 million keys each.

Unfortunately, executing the poisoning attack by Kornaropoulos et al. is heavily computationally intensive, so I had to run them with a fixed poisoning threshold of $p=0.0001$, thus generating 20,000 poisoning keys for a dataset of 200 million keys. This poisoning threshold can be considered to be relatively low, as previous work on poisoning attacks has used poisoning thresholds of up-to $p=0.20$.

Implementing a flexible microbenchmark for learned indexes

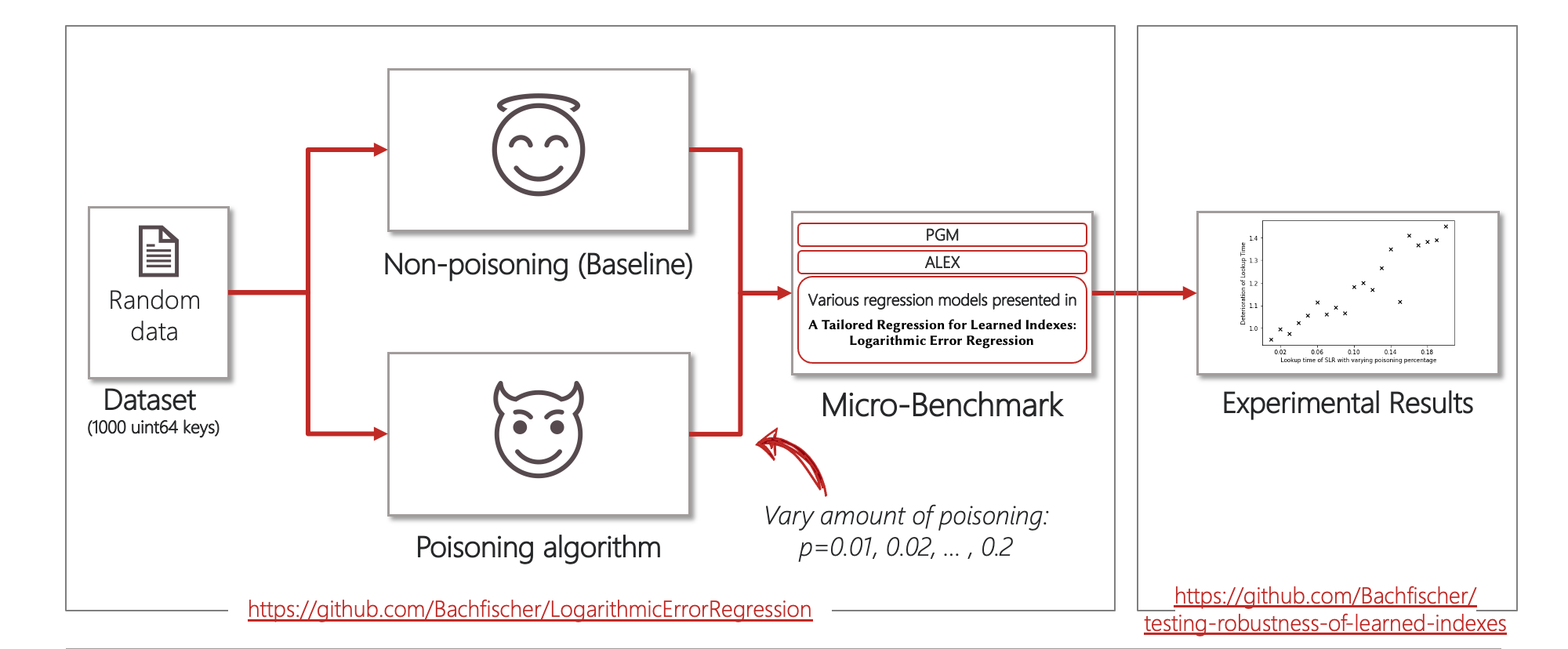

To test the robustness of learned indexes more rigorously, I have set-up a flexible microbenchmark that can be used to quickly evaluate the robustness of different index implementations against poisoning attacks. The microbenchmark is based on the source code that was published by Eppert et al. which I have extended to implement the CDF poisoning attack against different types of regression models and the learned index implementations ALEX and PGM-Index.

The corresponding source code can be found here: https://github.com/Bachfischer/LogarithmicErrorRegression.

Testing the robustness of learned indexes

To test the robustness of the learned indexes, I have generated a synthetic dataset of 1000 keys and ran the poisoning attack against each index implementation while varying the poisoning threshold from $p=0.01$ to $p=0.20$.

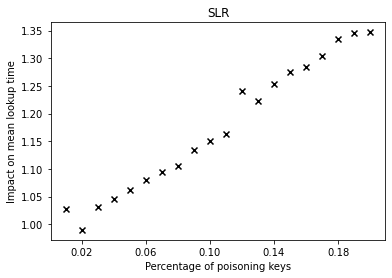

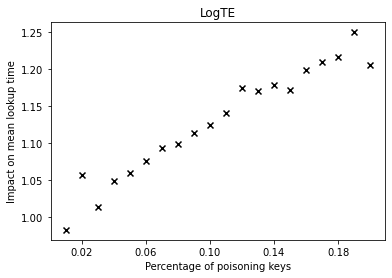

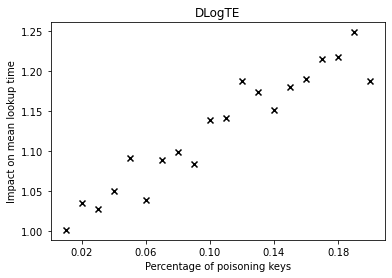

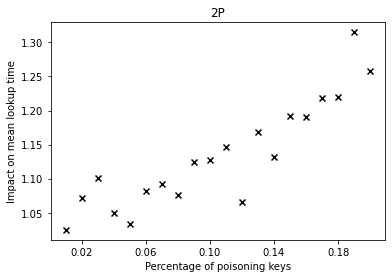

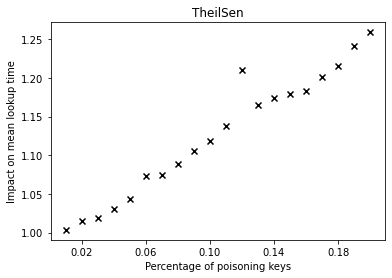

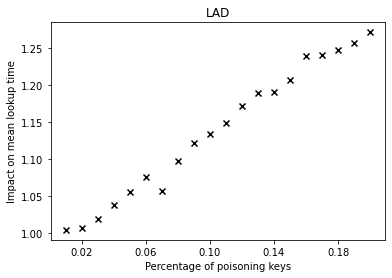

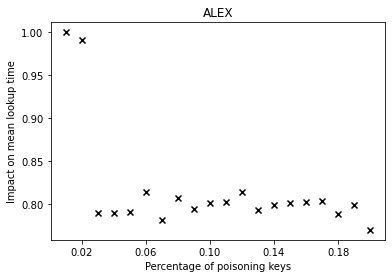

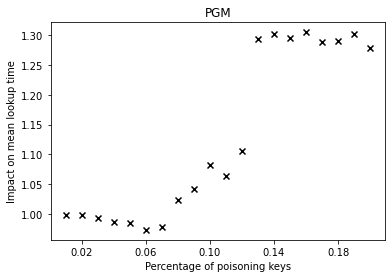

The graphs below show the performance deterioration calculated as the ratio between the mean lookup time in nanoseconds for the poisoned datasets and the legitimate (non-poisoned) dataset.

| SLR | LogTE | DLogTE | 2P |

|---|---|---|---|

|  |  |  |

| TheilSen | LAD | ALEX | PGM |

|---|---|---|---|

|  |  |  |

From the graphs, we can observe that simple linear regression (SLR) is particularly prone to the poisoning attack, as this regression model shows a steep increase in the mean lookup time when evaluated on the poisoned data.

The performance of the competitors that optimize a different error function such as LogTE, DLogTE and 2P (introduced in A Tailored Regression for Learned Indexes) are more robust against adversarial attacks. For these regression models, the mean lookup time remains relatively stable even when the poisoning threshold is increased substantially.

Because SLR is the de-facto standard in learned index structures and used internally by the ALEX and the PGM-Index implementations, we would expect that these two models also exhibit a relatively high performance deterioration when evaluated on the poisoned dataset. Surprisingly, ALEX does not show any significant performance impact, most likely due to the usage of gapped arrays that allow the model to easily capture outliers in the data (this effect can be likely attributed to the small keyset size). The performance of the PGM-Index deteriorates by a factor of up-to 1.3x.

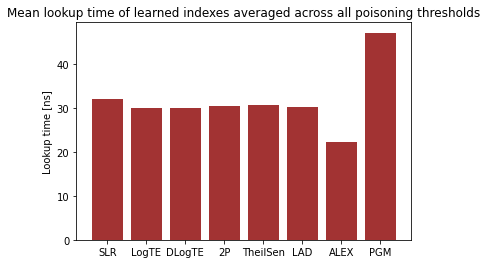

To put things into a broader perspective, I have also calculated the overall mean lookup time for the evaluated learned indexes (averaged across all experiments) in the graph below.

We can see that ALEX dominates all learned index structures. The performance of the regression models SLR, LogTE, DLogTE, 2P, TheilSen and LAD is also relatively similar, in a range between 30 - 40 nanoseconds.

In the experiments, PGM-Index performs worst with a mean lookup time of > 50 nanoseconds. This is most likely due to the fact that PGM-Index is optimized for large-scale data workloads and exhibits subpar performance in this microbenchmark because the dataset consists of only 1000 keys.

I consider the results from this research to be a highly interesting study of the robustness of learned index structures. The poisoning attack and microbenchmark described in this post are open-source and can be easily adapted for future research purposes. If you have any further thoughts or ideas, please let me know!