AI for Social Impact - A great leap forward

Published:

Over the past years, there have been major advancements in Artificial Intelligence and given the intense interest and investment in AI by industry and Academia, we believe that now is the time to focus our energies in applying AI to solve complex social problems in health, sustainability, community violence, and in assisting low resource communities.

This area of “AI for Social Impact” is a fast emerging field of scientific research and refers to the use of Artificial Intelligence to solve challenging problems in our society.

This blog post will show that in the area of AI for Social Impact, we are not only interested in algorithmic advancements, but also aim to deliver real-world social impact. This post is intended to provide interested researchers and practitioners with an understanding of this growing area of research and give an overview of some of the problems that can be solved by applying AI for Social Impact.

The “AI for Social Impact” data-to-deployment pipeline

Even though “AI for Social Impact” is a subdiscipline within AI, there are three key aspects in which “AI for Social Impact” differs from traditional AI research:

- Data collection may be costly and time-consuming.

- Problem modeling may require significant collaborations with domain experts.

- Assessing the social impact may require time-consuming and complex field studies.

This means that “AI for Social Impact” researchers have to invest their resources differently to make contributions to problems of great social importance.

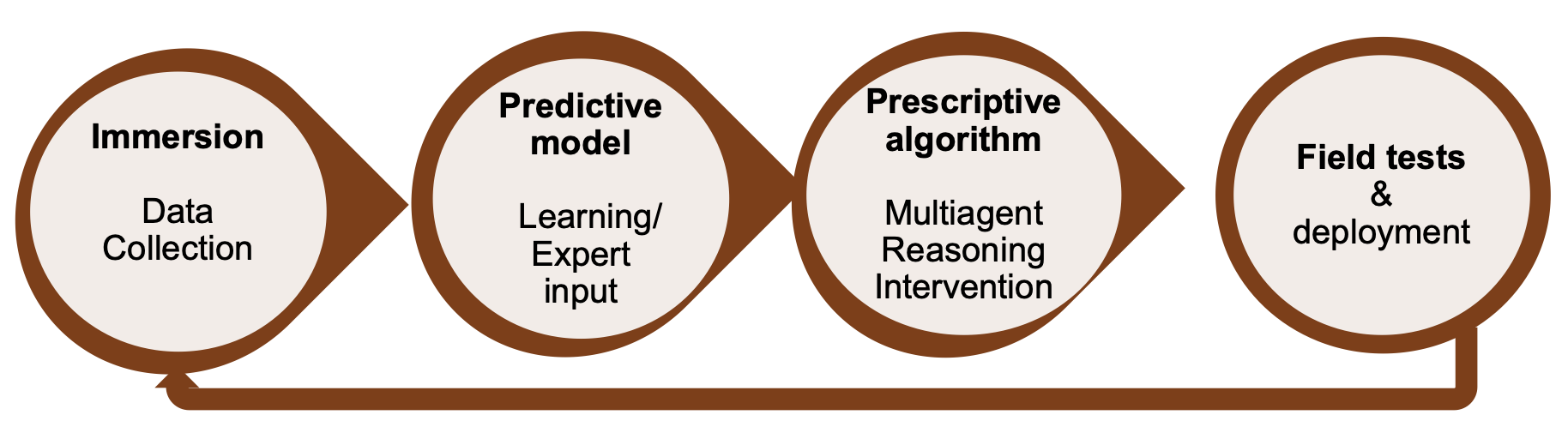

A high-level overview of a step-wise approach towards deploying an “AI for Social Impact” model has been laid out by Andrew Perrault et al. in their paper on “learning and planning in the data-to-deployment pipeline”. It consists of four steps:

1. Immersion

As a first step, immersion in the domain is crucial to get an understanding of the problems, constraints, and datasets. This may be a step that involves discussions with various stakeholders (including the impacted community). In this step, it is also important to build interdisciplinary partnerships and understand the challenges from the perspective of domain experts.

2. Predictive Model

Following an in-depth understanding of the problem situation, the next step is building a predictive model using machine learning or domain expert input. Such a predictive model may, for example, predict high-risk vs low-risk cases in a population.

3. Prescriptive algorithm

The next step is the prescriptive algorithm phase that plans interventions. Work on AI for social impact is often focused on domains where access to data is difficult (e.g., low resource communities or emerging market countries). Hence, the challenge is often to plan interventions despite that data is uncertain and sparse.

4. Field tests & deployment

The final step is field testing and deployment. This phase helps researchers to learn about the social impact as well as key limitations of the models and algorithms (and might even lead to fundamentally new research questions). Crucial for this phase is the interdisciplinary partnerships with the respective communities for immersion and field testing.

Case studies on various “AI for Social Impact” deployments

In this section, we want to give an overview of some exemplary problems that have already been tackled by “AI for Social Impact” research. This list is by no means exhaustive - we merely decided to focus on areas of research that we find interesting from both a societal as well as technical perspective.

Raising awareness about HIV among homeless youth using POMDPs

Target problem:

HIV is a serious threat to public health. Homeless youth is particularly susceptible to HIV spread because of injection drugs and unsafe sexual practices. It is therefore of major importance to raise awareness about HIV among homeless youth. To address this, various researchers have used techniques from sequential decision making and influence maximization.

Why AI is needed:

Youth social workers routinely launch “peer leader” programs to inform selected participants about HIV prevention, hoping that these peer leaders will spread the information to other homeless youth. These programs are often constrained by their available resources (financial and HR) and cannot reach out to every homeless youth. It is therefore important to select the “right” set of peer leaders.

Previously, service providers have used the degree centrality measure in a social graph to determine which person is the most popular youth. This is not necessarily the best selection method (e.g. in cases where the peer leaders might be unwilling to spread information).

Intervention overview:

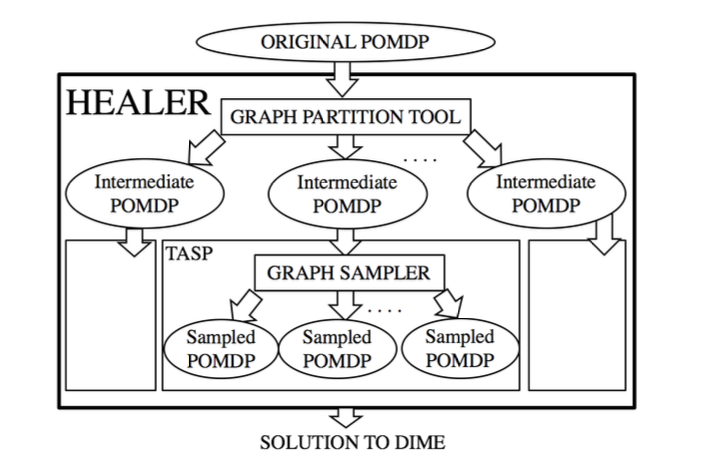

The authors formulate a planning problem in terms of a partially observable MDP (POMDP) in which they operate with the intent to maximize the influence on a social network. Since the existing POMDP solvers do not scale to the size of the problem at hand (a large “unobservable” social graph), Yadav et al. have proposed a hierarchical approach called HEALER which decomposes the POMDP into smaller ones.

HEALER then solves these smaller POMDPs using an approach called Tree Aggregation for Sequential Planning (based on a variant of the Upper Confidence Bounds algorithm applied to Trees, i.e. UCT) and subsequently aggregates the results. At each time step, the planning algorithm selects a small set of homeless youth as the “peer leader” who will participate in the program at the service provider.

Data used:

The dataset in this study is the social network connectivity, i.e. which homeless youths are friends with each other. This information was gathered by parsing the youth’s Facebook contact list to determine the friendship status. The data was further augmented based on reports gathered from the service providers who perform interviews with the homeless youths.

Resources needed:

Central to the success of the pilot study was the collaboration between the authors and homeless youth service providers. This helped to facilitate the recruitment of the youth and the implementation of the program. In addition to that, the engagement of social work researchers has also provided the necessary context and skills to communicate with the youth.

Deployment status:

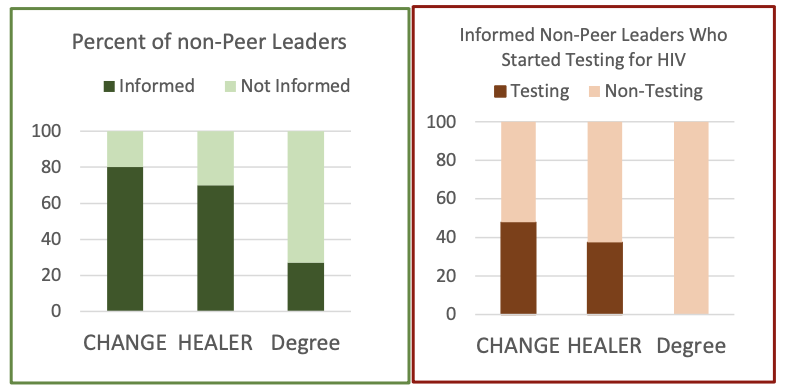

In spring 2016, the authors performed a pilot field test of HEALER, comparing it to the baseline of degree centrality. The experiment showed that HEALER is significantly more effective at spreading information - it reaches around 75% of non-peer leaders, compared to only 25% for the degree centrality approach. As a result, HEALER is more effective at causing youth to start testing for HIV: around 30-40% of the community began testing (compared to 0% for degree centrality).

References:

- Perrault, A., et al. (2019). AI for social impact: Learning and planning in the data-to-deployment pipeline.

- Yadav, A., et al. (2018). Bridging the Gap Between Theory and Practice in Influence Maximization: Raising Awareness about HIV among Homeless Youth.

- Yadav, A., et al. (2017). Influence maximization in the field: The arduous journey from emerging to deployed application.

- Yadav, A., et al. (2016). Using Social Networks to Aid Homeless Shelters: Dynamic Influence Maximization under Uncertainty.

Applying game theory to prevent poaching

Problem to be solved:

Wildlife poaching is a great threat to the ecological diversity of our planet. Because of the high profits to be made from poaching, poachers have become increasingly sophisticated. Rangers protect wildlife from poachers, but to be effective, it is important to design good patrol routes for the rangers. In a series of papers, researchers have developed and deployed a suite of game-theoretic tools called “PAWS” that simulate patrol routes to combat poaching.

Why AI is needed:

Patrollers in wildlife conservation areas have lots of experience conducting patrols. They design the patrol routes based on their knowledge and experience in the area. However, since the poachers are highly strategic in evading the patrollers, these patrol routes are very susceptible to gaming. While experience can help the patrollers, it may also keep the patrollers from going to underexplored areas where the poachings might be frequent. A game-theoretic planner for patrol routes can be useful in addressing these issues.

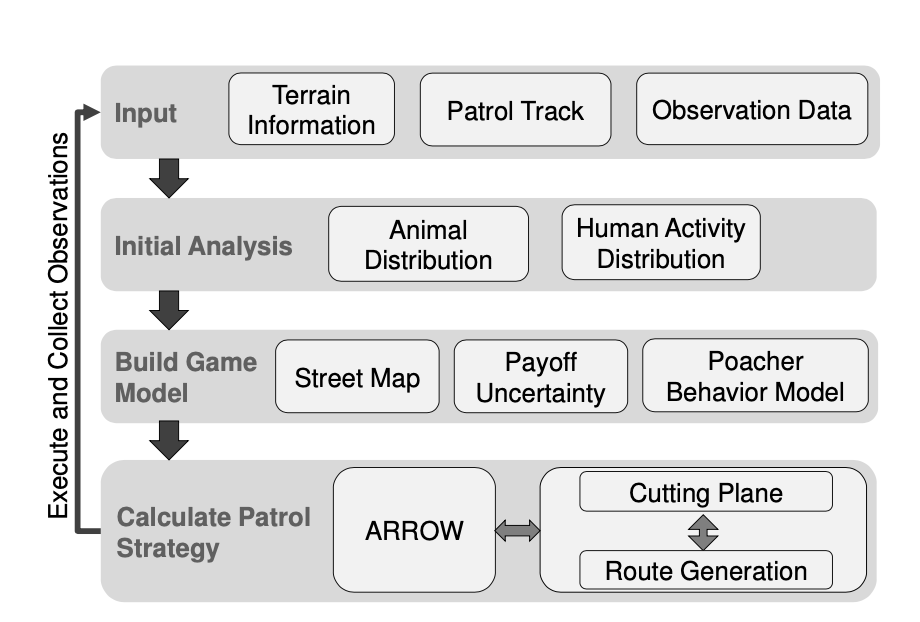

Intervention overview:

The authors propose PAWS (Protection Assistant for Wildlife Security), which is based on game-theoretic techniques usually applied in Stackelberg security games. PAWS models a two-player zero-sum game between an attacker (the poacher) and a defender (the patroller).

The authors use ML to learn poacher’s behavior patterns from historical data. The ML methods used have gone through several stages of development and involve (among others) a variant of decision tree ensembles, a hybrid model of decision trees and Markov random fields, as well as Gaussian Processes. Solving for the equilibrium of this game through mathematical programming gives an optimal patrol strategy for the patroller. Further enhancements to the system provide coordinated patrol plans for patrollers and use online learning to design patrols that trade-off exploitation and exploration.

Data used:

PAWS uses the animal activity data to estimate the animal density which plays a role in determining the payoff of each patrol route. PAWS also uses the poacher activity data to aid the poacher modeling. All these data and previous patrol tracks are obtained from the collaborating conservation agency. To consider the terrain and elevation information, PAWS also uses topographical data.

Resources needed:

The development of the PAWS system has been going on for several years and has involved multiple AI researchers. One of the most important factors for the successful deployment of PAWS in the wild has been the collaboration with conservation agencies. This has helped to identify suitable research problems and put the results in the field.

Deployment status:

PAWS has been field-tested in multiple conservation sites in Uganda, Cambodia, Malaysia, and China. The authors claim that PAWS proved to be effective in all these deployments, often leading the patrollers to patrol routes never used before but discovering poacher activities on those routes. In 2019, PAWS started a partnership with SMART (a popular wildlife conservation software). This partnership will hopefully allow PAWS to be scaled to over 800 wildlife conservation sites worldwide in the near-term future.

References:

- Fang, F., et al. (2017). PAWS—A deployed game-theoretic application to combat poaching.

- Fang, F., et al. (2016). Deploying PAWS: Field Optimization of the Protection Assistant for Wildlife Security.

- Fang, F., et al. (2016). Save the Wildlife, Save the Planet: Protection Assistant for Wildlife Security (PAWS) (Video on Youtube)

- Gholami, S., et al. (2017). Taking it for a test drive: a hybrid spatio-temporal model for wildlife poaching prediction evaluated through a controlled field test.

- Xu, L., et al. (2020). Dual-Mandate Patrols: Multi-Armed Bandits for Green Security.

- Xu, L., et al. (2020). Stay Ahead of Poachers: Illegal Wildlife Poaching Prediction and Patrol Planning Under Uncertainty with Field Test Evaluations (Short Version).

- Yang, R., et al. (2014). Adaptive resource allocation for wildlife protection against illegal poachers.

Public health interventions as a Multi-Armed Bandit (MAB) setting

Target problem:

In the global south, Community Health Workers (CHWs) play an important role in public health-care systems. CHWs complement primary health facilities by providing health education, screening, and basic emergency care in local communities. CHWs are often responsible for hundreds of patients, but only have access to limited resources (which restricts the number of patients that can be monitored and intervened each day). To maximize welfare, the CHWs’ resources need to be allocated effectively - this is commonly referred to as the health monitoring and intervention problem (HMIP).

Why AI is needed:

Existing solutions to optimize HMIP do not factor risk-sensitivity into their planning models. This can entail the risk of patients being ignored as they are seen as less important to be intervened upon. In traditional HMIP models, patients are intervened upon in a round-robin order which does not consider the level of care a patient requires and might lead to more interventions than really necessary.

Intervention overview:

The authors introduce Collapsing Bandit models, a subclass of restless multi-armed bandit models (RMABs) which they claim to be able to generalize better than previous RMABs. Each bandit’s arm represents a patient, and each time an arm is played, the MAB transitions into one of the following two states:

- Adhering to the tuberculosis medication and

- Not adhering to the medication.

The CHWs’ goal is to find a policy that maximizes the total reward across all arms. To find an optimal policy, the collapsing bandit model builds on the Whittle index technique and leverages Lagrangian relaxation to solve the optimization problem. As a result, the collapsing bandit model achieves a 3x-speedup compared to other RMAB techniques without impairing the model’s performance.

Data used:

The experiment makes use of a real-world healthcare dataset compiled by Killian et. all. This dataset contains data from 17.000 tuberculosis patients over 292 health centers in Mumbai, India, which have received a total of 2.1 million doses and needed to follow a 6-month medication plan.

Resources needed:

The local CHWs play an important role in building a bridge between health resources and local communities. With directly observed treatments, CHWs can observe and confirm directly that a patient is taking the prescribed medications. Despite this, the social stigma of public fear of illness and the financial burden on patients to travel to health facilities might still increase the likelihood that follow-up visits might be missed.

For this reason, digital adherence technology (DAT) plays an important role in supporting the eradication of diseases such as tuberculosis by observing the adherence to medication electronically. Patients can for example send a text message or provide a photo of their pillboxes to prove the drug intake, which allows CHWs to focus their limited time on high-risk patients.

Deployment status:

The authors have evaluated their algorithm on a variety of datasets, including real and synthetic data. In particular, Mate et al. used tuberculosis medication adherence data from Killian et. all. To the best of the knowledge of the authors of this blog post, no RMAB-based planning framework for health intervention has been put into production yet.

References:

- Killian, J. A., et al. (2019). Learning to prescribe interventions for tuberculosis patients using digital adherence data.

- Mate, A., et al. (2021). Risk-Aware Interventions in Public Health: Planning with Restless Multi-Armed Bandits.

- Mate, A., et al. (2020). Collapsing bandits and their application to public health interventions.

Outlook and further references

Looking into the future, we believe AI is of major importance for improving society and fighting social injustice. To that end, in pushing forward the agenda of §AI for Social Impact”, we need to engage in interdisciplinary collaborations and bring the benefits of AI to populations that have not benefited from it so far.

We hope that you found the case studies that we presented useful. In publishing this blog post, we wish to demonstrate the social impact that AI can have in the real world. From our perspective, we are only at the beginning of the journey.

Further References:

- Artificial Intelligence and Social Work by Milind Tambe, Eric Rice (Link)

- Harvard University Course “CS 288 AI for Social Impact” by Milind Tambe (Link)

- Artificial Intelligence for Social Good - A Survey by Zheyuan Ryan Shi, Claire Wang, Fei Fang (Link)

- Podcast: “Why AI Innovation and Social Impact Go Hand in Hand” with Milind Tambe (Link)

Authors:

- Matthias Bachfischer ([email protected])

- Michael Daschner ([email protected])